Ep. #05, The Verdict

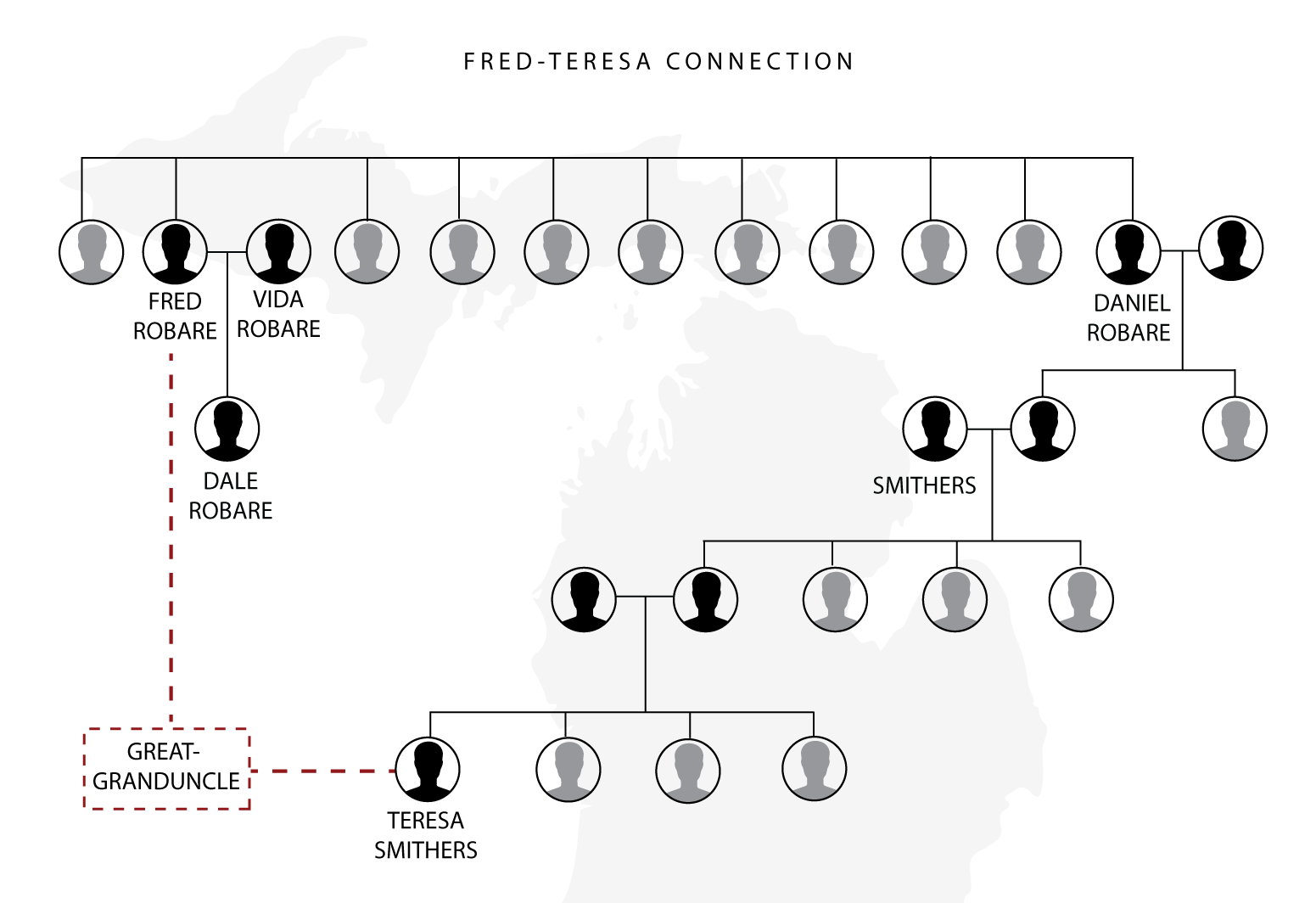

Podcast Copyright © 2021 by Keith Reeves, Jack Pokorny, and Margaret O’Neil. All Rights Reserved. Executive Producers: Keith Reeves and Maggie O’Neil. Producer: Jack Pokorny. Narrated and Written by Jack Pokorny. Original Music by Hee Won Park and Tommy Neil. Sandbox Atlas Blog Content Editors: Ben Meader and Emily Meader. Based on the meticulously researched book, The Case That Shocked the Country: The Unquiet Deaths of Vida Robare and Alexander McClay Williams by Samuel Michael Lemon, Ed.D. (2017). The podcast was generously supported by the Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility and the Program on Urban Inequality and Incarceration, both at Swarthmore College; the Swarthmore Black Alumni Network (SBAN); Keller, Lisgar & Williams, LLP. The producers wish to especially acknowledge the invaluable contributions of: Mrs. Susie Carter (Alexander’s sole surviving sibling); Dr. Sam Lemon (the great-grandson of Alexander’s original attorney); Teresa Smithers (a descendant of Fred Robare, Vida Robare’s husband); Osceola Perdue (Alexander’s great-niece) and her family; Attorney Robert C. Keller; Chris Rhoads; Sean Kelley, Annie Anderson, and Sally Elk, all of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site in Philadelphia.

[ 20 min read, 30 minute listen ]

8:45 P.M - Honorable W. R. Fronefield. President Judge. Sitting. 8:45 P.M. Jury brought into the courtroom, defendant present together with his counsel William H. Ridley Esq.[By the Clerk]: Members of the jury have you agreed upon a verdict?[Foreman of the Jury]: We have.[By the Clerk]: What say you in the issue joined between the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Alexander Williams, the prisoner at the bar.[The Foreman of the Jury]: Guilty.[By the Clerk] Do you find him guilty in manner and form as he stands indicted or not guilty?[Foreman of the jury]: Guilty of murder in the first degree.[By the Clerk]: What penalty?[The Foreman of the Jury]: Penalty: Death.[By the Clerk]: Members of the jury, hearken to your verdict as the court hath it recorded. Do you say, in the issue joined between the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Alexander Williams, the prisoner at the bar, that you find the prisoner guilty of murder in the first degree and fix the penalty at death in the manner provided by law, and so say you all?[The Jury]: We do.-Sam Lemon

Alexander’s criminal trial began in October, 1930 and a verdict was decided upon by the jury on January 7, 1931. In total, his trial lasted under 5 months. Today, death row cases can take years, often extended by many, many appeals. Alexander wasn’t given that time.

Ridley no doubt fought hard for Alexander’s life. He was up against a prosecution convinced they would land Alexander the death sentence from the moment they walked into the courtroom. Not only was the local community outraged at Vida’s death, but the case had attracted so much national attention that prosecutors probably thought, as prosecutors do today on high profile cases, that it would be the formative legal case of their careers. Up against such odds, Ridley at one point in the trial confessed to a newspaper that he believed Alexander committed the crime, but pleaded with the public and the jury to be lenient with his young defendant. He hoped they would empathize with Alexander’s story, and give him life in prison rather than sentencing him to death. Sam believes this might have been a strategic move on Ridley’s part. Ridley knew the chances of him winning the case were quite small. If he got Alexander life, they could always come back on appeal.

While that may be true, it may also be true that Alexander’s own defense attorney was convinced of his defendant’s guilt. It would explain why Ridley chose not to argue for an alternative story of what Alexander did on the day Vida died. In fact, he failed to even critique the story presented by the prosecution’s witnesses. Instead, He pointed to the cruelty and unusually extreme punishment administered at Glen Mills towards Alexander. [See footnote ^A] He used his four decades of legal experience and skill to make that single point to the jury.

After the jury sentenced Alexander to death, the black community was devastated by the verdict. From what I’ve heard from Sam, some people blamed Ridley for not winning Alexander’s freedom. The appeals process following the jury trial was the last chance to save Alexander’s life. The community decided to take Ridley off the case, and appoint a white attorney, Henry Goule, to represent Alexander. He argued on appeal that Alexander was insane. And he even had him tested by a psychologist. I don’t know what insane asylums were like in the1930’s, but if a boys reformatory school beat their charges back then, I can’t imagine Alexander had much say about this approach. As it was, the psychologist testified to Alexander’s sanity and his sentence was upheld. The process of legalizing Alexander’s death was in full motion.

Five months after the death sentence was first delivered, Alexander was incarcerated at Western State Penitentiary in the middle of rural Pennsylvania, roughly two hundred miles from his home. On June 8th, 1931 at 7:06 am, Alexander was electrocuted.

If Alexander really did kill Vida, what do we learn about history? In that lonely context, Dr. King’s arc would not bend towards justice. His, would be a dream unrealized, and Alexander’s story would be lost in the dark. Yet human nature inspires us, inexorably, to care about people we’ve never met. Interest in Alexander’s case wasn’t confined to his family members. Unknown to Sam, another person was also concerned about the fate of Vida Robare and Alexander Williams.

Teresa Smithers

Teresa Smithers is the great-grandniece of Fred Robare. Has done extensive research on her family history giving her a unique perspective on the case. Teresa is a writer and you can follow her work here.

Photograph taken by Shelby Dolche ©2020 by Keith Reeves

[Teresa Smithers]: Hello?[Jack Pokorny]: Hey is this Terese?[Teresa Smithers]: This is Teresa.[Jack Pokorny]: Hey, how's it going? This is Jack.[Teresa Smithers]: Good.[Jack Pokorny]: Good good.[Teresa Smithers]: Yes.[Jack Pokorny]: Hey, so it's good to finally talk to you.[Teresa Smithers]: Yeah finally connect.[Jack Pokorny]: Well, would you first introduce yourself?[Teresa Smithers]: Oh yes, I'm Theresa Smithers from Michigan and Fred Robare was my second great-grandfather. [Uncle][Jack Pokorny]: Okay, and did you ever know Fred?[Teresa Smithers]: No I did not. In fact I didn't know anybody on that line of my family because my father died when I was very young. And so we were disconnected from that family for all my life. When I became an adult I wanted to know more about my father, so I started researching his family history and that's the way I learned about the Robares.[Jack Pokorny]: Wow. So can you share whatever you know with me? Or anything you remember or heard from your side of the family about Fred Robare?[Teresa Smithers]: Yes. When I read about this story, read the newspaper accounts—I'm a fan of reading old newspapers too, and when I read all the newspaper accounts, I was really intrigued with the story because it looked to me, just because I got the hindsight of living in today's world, that it looked like domestic violence to me.[Jack Pokorny]: And you didn't grow up hearing about the case with Alexander at all?[Teresa Smithers]: No I did not. I knew my great-grandfather was Fred's brother, Daniel, and he was a very rough character, and in fact, he had lost my grandmother, she was given away to people. Even when people—when the kids saw Daniel in later years, they would hide from him because they were afraid of him, because he was a pretty rough character and I think they all were pretty rough, just from what I've read about them. I know another brother, Edgar, went to jail for murder. [See footnote ^B] So it was just a rough family, a lumberjack family up in the up north woods.

“Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”

[Jack Pokorny]: Up in Northern Michigan?[Teresa Smithers]: Yes, in Northern Michigan.[Jack Pokorny]: How would you characterize, like, a ‘rough family’?[Teresa Smithers]: A lot of beatings, because that probably made men out of them. I know the boys all got in trouble with the law. They cannot keep a marriage together. The first marriage, usually the second, third or fourth, they figured out to act more socially acceptable. But I think they grew up thinking that it was normal to express their anger in violent ways.[Jack Pokorny]: What do you think the family culture was like between Fred and Vida Robare? If you can talk about that.[Teresa Smithers]: Yes. They actually got a divorced in Saginaw, Michigan. They had two children that died in infancy, one of illness and one of malnutrition. He didn't care for the family. When they got the divorce, she said he was always trying—he was always threatening to throw them out on the street. At that time it was just her and the only son that survived, and he was running around down there openly and threatening to throw her out, and not taking care of the family. So she divorced him. But then I found where they had applied for a new marriage license in Baltimore, Maryland just before they went to Pennsylvania. And in hearing that you know and knowing what she had written about the divorce account, I felt like I knew why she did it. She had a son that was growing up and she wanted him to have his father. And so she was giving him another chance. I've been through it, we've all been through it. So I was sure that what was in her mind was that she was going to give him another chance because he made promises. And I think they were—he was a very charming personal person—he just didn't know how to handle his anger, he didn't know how to treat people.[Jack Pokorny]: Yeah.[Teresa Smithers]: And so that’s what came out.

I asked Sam about his thoughts on this revelation.

[Sam Lemon]: For Vida Robare to sue for a divorce on the grounds of extreme violence in 1921 was extremely unusual and amazingly heroic for a woman to do. It wasn't much before that that people were still using the rule of thumb in which it was okay to beat your wife with a stick as long as it wasn't any thicker than your thumb. So this was a courageous young woman who overcame physical violence, the loss of two infants within a three year period, this husband who couldn't keep a job and who was physically abusive to her. She was just really a remarkable person who deserved much better.

[Jack Pokorny]: Did Sam ever talk to you about the physical abuse that Alexander probably experienced from Fred? Do you think Vida had a role? Or what was her role between Fred and Alexander and their relationship?[Teresa Smithers]: Vida was very well liked and she was a house mother. And I Think she was a really kind person too from what I've read about her. She was very kind and probably very—I'm sure she was a very good mother and probably very sad that she lost two kids. But I had heard that in the court transcripts it said that Fred had kicked Alexander once, and that doesn't surprise me, and Vida came to his defense and he hit on her, which sounds about the way Fred would have acted. It's what I would have expected anyway. And I don't see Alexander, if he was trying to get revenge, I do not see him at all hurting the only person who was kind to him. It just—that just doesn't make sense because Vida, I think, was a very kind person. And she protected him that time, she came to his defense and I'm sure he remembered that. It's not Alexander's M.O. anyway because he wasn't the type to confront anybody. If he was going to get revenge on Fred, he would have started the fire in the apartment. He liked fires, he liked starting fires and that was something he could do without actually confronting somebody. I just don't see him doing it.[Jack Pokorny]: So you believe Fred Robare killed his wife Vida?[Teresa Smithers]: I do. I think either Fred was messing around with somebody’s wife at the school, or doing something else that was a little shady, and I think she was threatening to either leave him or report him, and both would have made him angry. He kind of—you know obviously he wanted to marry her again, he's trying to stay with her. I think it would have made him very angry and he would know how to stop her from doing that. And I could—also she was a very strong woman too, and Alexander, I do not think he could have overcome her. I just don't think Alexander did it. I really don't. I always did feel that way. I don't have any proof and I don't have any proof that Fred did do it. I'm just— just by looking at what we know now about domestic violence I think—and what I know about the Robare family at that time, I think he did. [See footnote ^C]

If Fred really did kill his wife, as Tereasa believes, that leaves us with the unsettling punch to the gut reality that Alexander’s confessions, and maybe even his overall involvement in Vida’s death, was fabricated. Maybe he wasn’t even in Cottage 5 the day of the murder. Someone would have had to force Alexander to give the confessions, constructing the violent imagery and wording to better convince the jury.

The two detectives on the case, Oliver N. Smith and Michael Trestrall, both members of the KKK, were involved in taking Alexander’s confessions as was the prosecution, Mr. McCarter, who issued the orders for another confession to be extracted. Thinking farther back, so was Major Hickman, the school’s superintendent.

The most dis-spiriting part for me is the magnitude of the potential coverup, involving the Glen Mills administration, the top prosecutor from Philadelphia, the state police, the county court system, and Alexander’s judge and prosecution. Whether or not they were involved directly, they nevertheless witnessed as Sam like to call it, the legal lynching of Alexander. Through this lens, Alexander was used as an example to maintain social control over the black community. The extreme cruelty they put him through was manipulation through terror.

Yet, even in the extremity of his case, Alexander’s legal battle is representative of the violence and prejudice against black and brown people that hangs like a superstructure of oppression into the present day. Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, to name just a few—these deaths are all contemporary legal lynchings. The form of discrimination has changed in some cases, but the basic reality remains. And trauma gets passed on.

[Jack Pokorny]: Can you tell me how Fred Robare died in the end?[Teresa Smithers]: He died in 1953, I believe he had a heart attack if I remember right, it was natural causes. In 1953 in California. He moved right after—right after he was able to leave Pennsylvania, once he got the body it took her to Michigan and had her buried there. And then she,—then he, left his son with relatives and then he went to Maryland where he met his second wife. He was down there with his brother and then they moved from Maryland to California which is where they lived until he died. I think she also filed for divorce after several years but I don't remember if it got finalized or not. He may have died before it did, I can't remember the date on that.[Jack Pokorny]: Have you ever gotten any records of her, or she is?[Teresa Smithers]: Her name was Catherine Smith and I have tried to look some stuff up about her but I haven't found too awful much. When she became his wife I guess she was pretty quiet. They had,—well they didn’t have a son, Vida and Fred had a son, Dale Robare, that they left up north. Dale tried—Dale went down to California, you could tell he was always trying to have a relationship with his father but it never worked out that way for him. He was always living with somebody else, down the road or wherever. And he's really had a vagabond life, kind of just moved from here to there. [He] got into trouble but he didn't seem to be a bad kid. I think he just—he just went through a real trauma and never really healed from it. But he got in trouble. He robbed a hotel. He pretended to have a gun but he didn't. He just pretended that he did, and they took the money but then he felt bad about it so he turned himself in to the police in Arizona. And that was in the newspaper they said was kind of comical because usually robbers don't come up and say “hey they want me in California”. But that was how he was, you know? And he didn't have any children. He pretty much just drank and smoked his way through life until he married late in life and well late in his life anyway and died soon after.[Jack Pokorny]: What did he die from?[Teresa Smithers]: I got his death certificate, and he died from a—I can’t remember the exact wording they used but it was complications with the lungs. It sounded like from smoking, emphysema or something like that.[Jack Pokorny]: So last time we kind of talked about, that you—you know, this kind of rumor in your family. The curse on that side of your family.[Teresa Smithers]: We've had a lot of young men in our family die young and that's where it came from. My dad died young, he was only 26, his brother lived longer but he died by 58. The curse was that no man would live past 60, you know. So we just— at least that's what they said. My kids started picking it up and saying the same thing and I didn't want them to think that there was no hope for our family, there is. There’s hope for all families and that's not what was happening, it wasn't a curse. The only curses, you know [are]: the one that you put on yourself. And so that's one reason that I wanted to research this out. And also, if there was—the curse would be what family does to itself then this could help heal it. Because I don't call it a curse as magical it's just what happens in a family, gets carried down generation to generation. And if you've had bad comedown where you inherited drinking or abuse or divorce and early death, you can just as easily inherit good things happening in your family and helping others and making the world a better place. And that's what I wanted my kids to inherit. I didn’t want them to inherit the negative side. So that's why I wanted to do this. Also besides that young boy needed justice. You know, if you have a trauma and you bury it, you're never going to heal from it if you don't face it. It's just one of those monsters in the dark, that once you face it, it ain't so bad. We get over it. Eventually love conquers all, and love really does conquer all. My mother always used to say that you know, ‘the devil was the Prince of this earth’. I don’t believe that at all, because if evil was in charge there would be no love there would be no goodness left. So you—the fact that there is kindness and love and goodness in this world means that love is stronger than evil and a lot stronger and so that's what we need to focus on. Face the evil, admit to it, fix it and move on and if you can't fix it, just move on. That's just my opinion. It takes a while sometimes but justice does get done. It all evens out in the end. That's what it's supposed to do.

Does Dr. King’s arc include punishing the guilty for their crimes? What about the descendants of the guilty? There’s a frightening parity between Alexander’s own death and Fred’s male family members dying early in life. Whatever that means, one truth that I’ve come away from this with is this striking continuity of pain and suffering, between people and families and across generations. Sam has spent over thirty years thinking about and feeling the consequences of Alexander’s death because of his grandfather. Tereasa is thinking about it too, because of Fred.

Alexander has but one immediate surviving family member, his sister Susy Carter. She lives not far from Glen Mills in Chester, Pennsylvania. On a rainy weekend afternoon last fall, I drove to her house with Sam. When we arrived, seated around her dining room table, was about five or six family members. In the living room, separated from the dining room by a stairwell, was Susy Carter seated in an armchair.

Susy Carter receiving flowers and a kiss on cheek from Dr. Keith Reeves.

Photograph by Shelby Dolche ©2020 by Keith Reeves

[Susy Carter]: My name is Susy Carter. I'm the daughter of John and Osceola Williams and I live in Chester, Pennsylvania. I'm a young woman of eighty eight years.[Jack Pokorny]: So I'm curious, what are your earliest memories of Alexander or of mentions of Alexander.[Susy Carter]: Well I was one year old when he died. I have no memories of him at all. But I listened to my mom and dad whenever they talked about it, that he never killed the woman. And when they talked about a matron I thought that this was something that happened to a postal Matron. I had no idea.[Jack Pokorny]: Did they talk about Alexander or about Vida, or about what happened to Alexander very much?[Susy Carter]: No, because I knew that he was killed because of it, but that's about all. Whenever they were talking about something private they would tell us to go outside and play. There was 13 children. Now Alexander was the oldest.[Jack Pokorny]: So like you said they didn't they didn't like to talk about it very much right?[Susy Carter]: No.[Jack Pokorny]: No, so how do you think your family dealt with Alexander's death?[Susy Carter]: Why I just lost a son. That was a terrible thing. And so I can't imagine how my mother must've felt. To lose a son that she knew, she knew in her heart that he did not do this.[Jack Pokorny]: So before Alexander went to Glen Mills when he was still at home, what did the family say about who he was as a person?[Susy Carter]: I have no idea they never—I mean an exe—electrocution was not something that you bragged about or talked about. So whenever they talked about it, it was something that was hush hush.[Jack Pokorny]: Has that changed, now?[Susy Carter]: Has it changed now? Well I'm the only one alive.[Jack Pokorny]: Do you wish that people talked about it more?[Susy Carter]: Yeah, every year that I've been grown—Alexander McClay—every year, they write this in the paper. I had no idea they were talking about my brother.[Jack Pokorny]: What did they say in the paper about him?[Susy Carter]: That he was executed. The youngest child in the state to be executed. I mean they killed him on purpose.[Jack Pokorny]: Why? Why would they kill him on purpose?[Susy Carter]: I have no idea. The only thing I can think of —that handprint on the wall. Whose was it? It sure wasn't his. So why wasn't it mentioned at the trial? And her cousin sent a picture of him. And if you look at it don't you think he has a black eye? Why would that be? They probably beat him to death. They probably beat him up, making him sign those papers. There's a lot I hate in the world and I don't know and I don't understand how it could happen except that Satan loves it. Satan loves it.[Jack Pokorny]: Can you tell me a little bit about your parents?[Susy Carter]: My dad loved my mother and he worked hard.[Jack Pokorny]: What did he do?[Susy Carter]: He was a disciplinarian but he loved us all. And he took care of us the best way he could. After this happened—I was about two years old when my mom moved to Glen Riddle. We were the only black kids in the school. But when my dad found out my mother had diabetes, he would bring her home a honeydew. And he come, he’d have to walk home from work, and he would come home with a handful of—he had big hands— had a handful of violets, and he would bring it home and give it to her. He took care of us. And he had a big garden and every—my mother would put up every thing you can imagine. She'd make jellies and jams and we never thought we were poor because we always had something to eat. And then in wintertime she'd go down, say ‘go down in the cellar and bring up the peach jam’ and she would have hot bread because we had to—we then—we had an outhouse, no electric, had a battery [words unknown]. And we were happy. We had a happy family. And he would have been just like us. He would have been happy.[Jack Pokorny]: One of the things that this podcast is kind of thinking about, is Dr. Martin Luther King's—he said this quote that’s, “that the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice.”[Susy Carter]: We want justice. Complete justice. We want it completed.[Jack Pokorny]: What does complete justice look like for you?[Susy Carter]: That he would be exonerated completely, not just expunged, not just taken a record off, let people know that this was done and needs to be brought out, it needs to be clean, the record needs to be. And whoever did it, needs to be exposed. All of it needs to be exposed. The Bible says, God made out of one man every nation, meant to dwell on the surface of the earth. That means you're my son, that means we're brothers and sisters.

Swing low, sweet chariot

Coming for to carry me home

Swing low, sweet chariot

Coming for to carry me home

I looked over Jordan and what did I see

Coming for to carry me home

A band of angels are coming after me

Coming for to carry me home

Swing low, sweet chariot

Coming for to carry me home

Swing low, sweet chariot

Coming for to carry me home

Excerpt of Swing Low Sweet Chariot —Sung by Sam Lemon In 2017, Sam reached out to Rob Keller, the lawyer you heard a couple episodes back, to try and get Alexander an expungement. Keller is a local expert in expungement hearings, so it was a big deal to have him on the case. The expungement would remove Alexander’s criminal record from his file, while not fully exonerating him.

In our final episode, we’ll learn what happened the day of the expungement trial. And finally come to terms with the legacy of Glen Mills, Alexander’s place in history, and the arc of the moral universe. Thanks for listening, and stay with us.

Footnotes:

A. On Older Cases of Child Maltreat at Glen Mills. Though the punishments and abuses Alexander underwent at school, including the ill treatment by Fred went unreported, the treatment of those being kept there had been questioned before. It was decided in most cases that there wasn’t enough evidence to support any charges, or they believed the boys to be lying. On March 1, 1913, the Chester Times reported on the case of a boy named George Proud Jr., who said he was beaten and kicked by the employees of the school, Strohm and Rees. The article reports “Outside of the Boyd, and Rees and Strohm cases, which are now in the hands of the court, the committee feels entirely justified in reporting that the evidence disproves every charge of cruel treatment of the boys at Glen Mills at the hands of officers and employees.”

The Chester Times on March 25,1913 reported on the trial for Rees and Strohm trial which was underway. Thomas B. Rees, and George Strohm, had been accused by George Proud Jr of abuse. Both denied all allegations, which had included kicking Proud, and throwing stones at Prouds head while out in the fields. Ree’s also denied refusing to send a letter from George to his mother. A former inmate, Howard De Shield, corroborated Proud’s story, yet the prosecution pointed out that being a former inmate of Glen Mills on two separate occasions, that he was not known for telling the truth. Testimonies from multiple staff members stated that both Strohm and Rees were people of good character. Five fellow inmates also were brought before the court and said they had no knowledge of the abuse. It was further stated that “the evidence was not sufficient evidence to substantiate the charges made by Mr. Proud, to warrant any further investigation…” Both Strohm and Rees were found not guilty.

B. On Edgar Robare. Edgar Robare was Fred Robare’s younger brother. He was sentenced on April 15, 1922 to life in prison for murdering Botolf Norbergon. Edgar was working alongside Oscar Settergren in a robbery attempt which ended in the bludgeoning of Norbergon to death. The Escanaba Daily Press reports on June 13, 1922, that “the two men had believed that Nordberg had $600 on his person with which he expected to pay off a mortgage on this farm.” It was later found out the men obtained just $30. On the 6th of September 1922 Edgar, using a board as a latter, escaped Marquette prison where he was being held. He was recaptured on the 9th of September that same week in the woods 7 miles from the prison. Edgar tried to appeal to the courts multiple times through out his sentence. Edgar Robare’s sentence was commuted by Michigan Governor G. Mennen Williams after 31 years in prison made him eligible for parole in 1953.

C. On Other Murderer Possibilities. Throughout the investigation there were few alternatives to the theory that Alexander was the perpetrator they were looking for. Though there were others who were looked at briefly. Harry Bunio was questioned in the murder on October 6th 1930. He had a revolver as well as an ice pick on his person but it was found that the ice pick wasn’t the one used to kill Vida.

Another idea was posed early on that Vida was killed by a woman. It was published in multiple papers that they were on the lookout for a female. An anonymous woman who worked at Glen Mills claimed that she either knew, or had strong suspicions on murderer but refused to say who for fear of her own life. Gouley, Alexander’s defense lawyer after Ridley, tried to get Alexander's sentence changed by bringing in Earl Kartzer. A warrant had been sworn out by Mrs. Osceola Williams, Alexander's mother for Earls arrest. Earl was arrested for being an accessory to the murder. It was claimed that Kartzer had been the one to suggest the crime. Due to the late timing, The petition to stay Alexander’s execution was refused and all testimony surrounding Earl was dismissed as untrue.

The idea that Fred was involved was quickly dismissed by law enforcement of the time. Looking into Fred’s past though, as Teresa does, sheds more light on his character. His tumultuous relationship with Vida which included a divorce in addition to his known volatile behavior makes him a possibility as the one who committed the crime.