#13 Greetings from Mount Desert Island

Gus Phillips creates maps and postcards of his island home

Cathy Jewitt, Author and Editor

John Meader, Photo and Content Editor

Augustus Phillips postcard #372 Greetings from Mt. Desert Island.

To listen to the text, click the player above. To enlarge any photograph or map simply click on the photograph.

It’s 1967 and Gus is shooting photos of Mount Desert Island (MDI) from the air, land, and sea. After the film is developed, and the frames are mounted as individual slides, Gus decides which ones he will send to be printed as postcards.

Often as many as ten to twenty slides feature similar shots of a subject; comparing those shots, and choosing the one he deems printable is a time-consuming part of the process. When relatives visit him and his wife Mary, he often seeks their input, turning this part of his work into an evening’s entertainment.

After dinner—often a meal of fresh fish (with the grandchildren hoping it isn’t finnan haddie) and steamed vegetables, or haddock chowder and yeast rolls (always a hit)—as the evening’s light begins to fade, Gus sets up his Kodak carousel projector and screen in the living room. Earlier in the day he filled up his 80-slot carousels with slides. His projector has already been loaded with the first carousel when he invites us to join him in the darkened living room. Although he sits in a straight back wooden chair, we are encouraged to make ourselves comfortable on the couch or in one of the floral-upholstered wingback armchairs. We settle in, and the slide show begins.

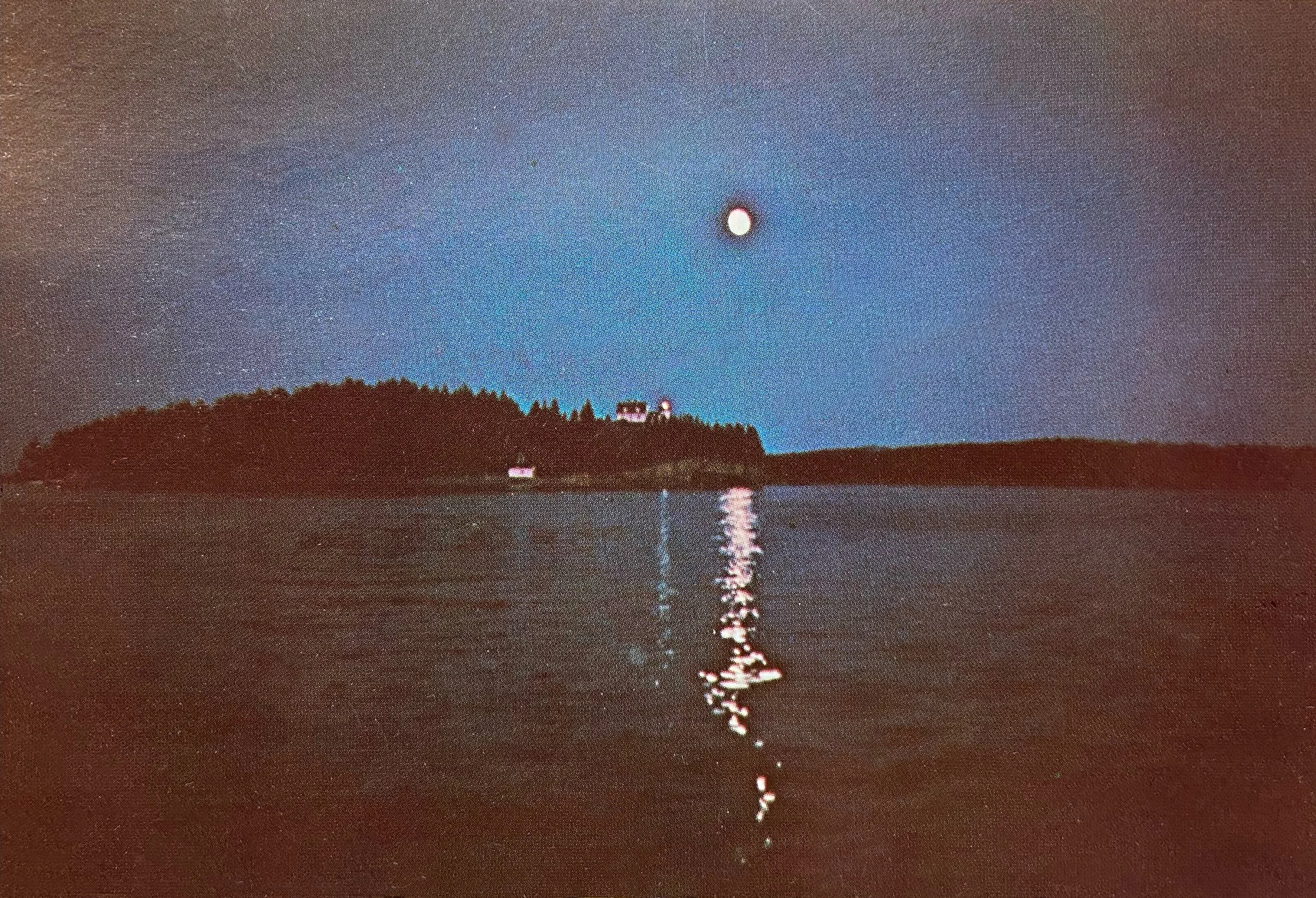

As twenty slides of the lighthouse on Bear Island under the moonlight appear in succession on the screen, the adults discuss the pros and cons of shots. Which frame best captures the subject? Why that one? Why not that one? The grandkids just want to see a different picture.

Gus’s Postcards of Bear Island Light from left to right: #159 Bear Island under Moonlight, #74 Bear Island and Northeast Aerial, #440 Bear Island Aerial.

New images follow, and the click of dropping slides indicates a series of similar shots of an aerial view. What appears to be the best photograph reveals that Gus has inadvertently captured part of the plane's wing in the frame. This elicits substantial discussion. In the end some of those wing shots make it onto postcards. Time constraints and flying fees preclude a second photo flight, even though Gus would like nothing better than to schedule one.

Thrilled to stay up beyond our bedtimes, my brother and I sat through numerous evenings watching Grampy’s slide shows. Occasionally, we chimed in with our own opinions. The cadence of slides dropping into the projector in the darkened room usually lulled us to sleep, resulting in our missing the end of the evening’s slideshow. ^1

In 1967, Gus’s Mount Desert Island postcards can be found in businesses from Bar Harbor to Bass Harbor, filling rotating floor racks in gift shops or sitting on restaurant check-out counters. Acadia National Park has continued to draw visitors to the island, with over a million people predicted to visit in 1967. ^2

Subsequently, Gus is kept busy filling orders and re-orders, and making frequent deliveries. Many of his cards feature MDI’s stunning ocean and mountain scenery. There are postcards of the iconic steamed red lobsters, lighthouses, and small-town streets lined with enticing gift shops.

Gus’s postcards of MDI from left to right:

first row: #67 Bar Harbor, #153 Thunder Hole, #68 Baker Island, #90 Bass Harbor Country Store

second row: #80 Sand Beach, #161 Bass Harbor Light, #95 Bar Harbor Lobster Wharf, #149 Acadia Headlands

third row: The Moorings Inn, Manset, #221 Lobster, #436 Jordan Pond and the Bubbles, #43 The Bluenose Ferry

Rather than taking photographs, many tourists buy postcards as treasured souvenirs, building large collections often discovered by relatives decades later. Many more postcards are mailed, sent with a message and a color photo to admire, bridging the distance between sender and recipient.

Curious to discover what messages tourists were penning on Phillips postcards in the 1960s and 1970s, we looked at vintage postcards on Ebay and CardCow where we found several. One postmarked July 1966, read “Maine is no good for swimming - too cold! But great for beaching and hiking.”^3 Weather was a recurring topic. A July 1967 card said “We have been here a week and not much sun but have had two nice baths on Sand Beach.”^4

Gus’s postcard #52 Breaking Waves mailed in 1970, read “Today it is raining so we will go to Bar Harbor to visit the shops and to find some things we have not seen before.”^5

Those messages could have been written this past July, as many visitors to Mount Desert Island still find the water more than “refreshingly cold,” preferring to sunbathe or look for shells, especially at Sand and Seal Harbor Beaches. A rainy day still swells the pedestrian traffic in Bar Harbor, as visitors pop in and out of shops looking for momentos and gifts. A fourth postcard from June 21, 1967, reads: “We are frozen in the midst of a wild storm. First day of summer?” ^6

During that July of 1967, as tourists send postcards and Gus fills postcard orders, he admits to himself that his working life is chock-full. He celebrated his 69th birthday in May, but he can’t afford to slow down. Over a million visitors are expected to explore Acadia this year, and the large majority of them arrive during the short summer season. He's keeping his Rambler in good working order, as he is traveling around the island and statewide delivering orders. Many businesses make most of their profits during the warm summer months. Few of the business owners order enough stock to cover the entire season, preferring to reorder only when it’s clear what’s selling the best. Driving around the state tires him out, but he has made friends everywhere over the years, and exchanging stories and local news keeps it enjoyable.

With carpentry and woodworking jobs on the island that require physical stamina and further time commitments from him, Gus has to juggle his daily schedule. He appreciates the respite that delivery trips provide. Best of all, when his wife Mary accompanies him, it’s almost like a vacation. Well, at least Mary enjoys a break from cooking.

This decade certainly started off poorly for Gus when his older brother Luther died on Christmas Eve in 1960. Missing Luther, and carrying on the map and postcard business by himself, has been overwhelming at times. Maybe the added stress contributed to his heart attack in 1961. And just as he was recovering, laryngitis laid him low. These setbacks forced Gus to slow down, for a while.

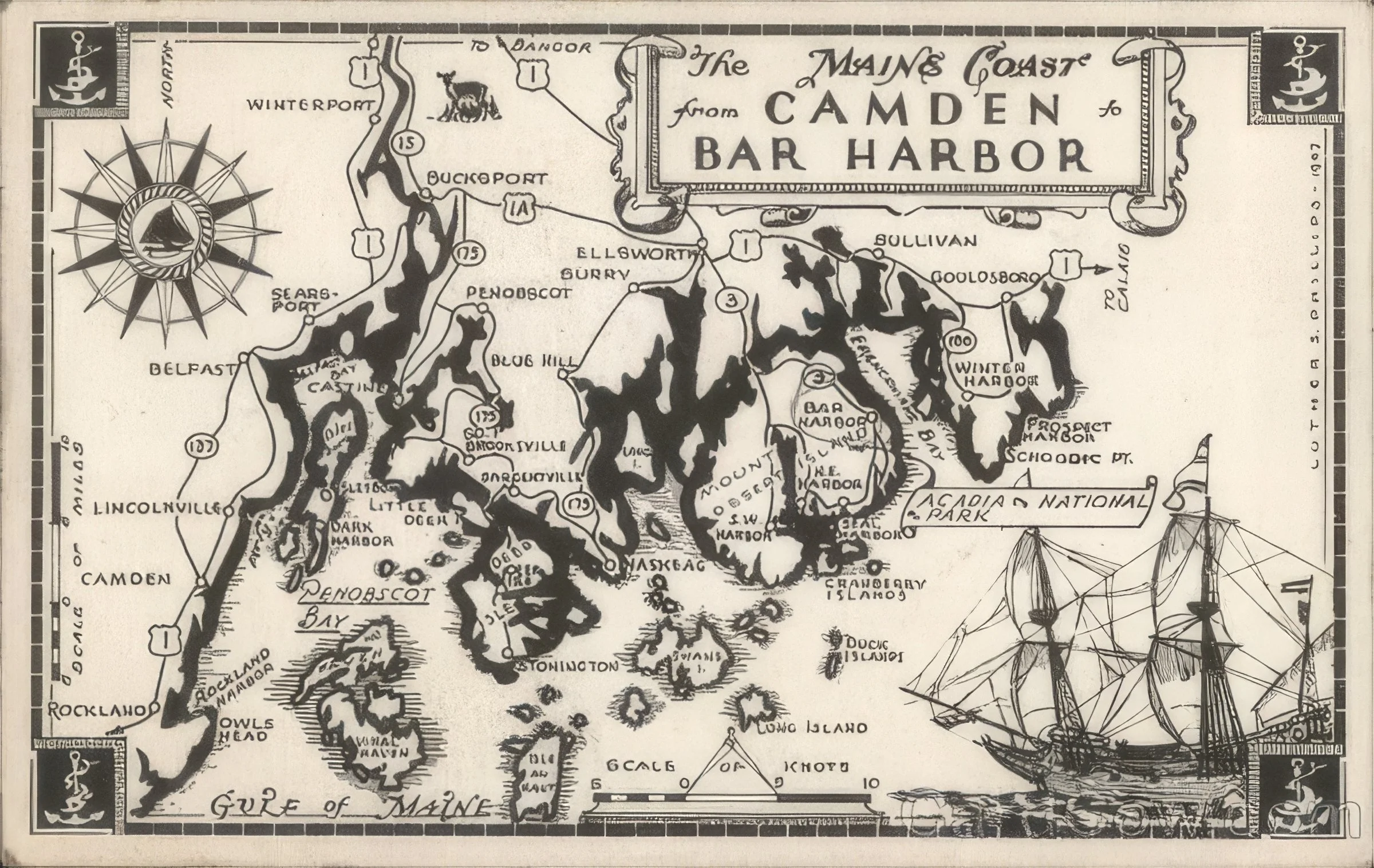

Map postcards from left to right: Luther’s 1947 The Maine Coast from Camden to Bar Harbor, Gus’s 1963 revised version, and Gus’s own 1963 Map of Mount Desert Island.

Note: Gus’s revision not only adds color, but also extends the coastline from Prospect Harbor to just beyond Cape Split.

Once back on his feet, Gus kept his brother’s maps in circulation, revising and updating some of them, while adding several new ones. He has expanded Luther’s postcard business, adding hundreds of his own. Almost all of Gus’s postcards are in color now. He also took on woodworking and woodcarving projects at Asticou and Thuya Gardens, for his cousin Charles Savage.

Charles designed the two gardens in Northeast Harbor. Asticou Azaela Garden was constructed between 1956-57. Thuya Garden followed, opening in 1962. As Gus added Asticou and Thuya woodworking and carpentry jobs to his schedule, he recorded daily work specifics in small logbooks. He searched Asticou Hill to find cedar which he milled into tongue and groove boards for fencing. With this wood he built the fence to surround the developing garden at Thuya. Gus’s craftsmanship answered the practicality of keeping deer out of the garden while aesthetically enhancing the garden’s hillside landscape. He fashioned garden resting shelters, a well house to protect the old spring on the Thuya property, and a map house beside the woods path that connected both the Azalea and Thuya Gardens. However, the entrance gates to Thuya Garden are Gus’s masterwork in wood.

From left to right: cedar fence at Asticou, photo by John Meader; resting shelter at Thuya, Gus’s postcard #16; map house on trail between Asticou and Thuya Gardens, photo by John Meader; Gus building well house over the spring at Thuya, photo courtesy of Northeast Harbor Library; Thuya Gates, Gus’s postcard #90.

Before Thuya Garden opened, Gus carved images of local floral and fauna on 48 individual cedar panels, which he set into a double-doored gate that he built to welcome visitors into the garden. In a small logbook, Gus detailed the hours he spent carving individual panels and constructing the gate itself. In February 1962, Gus recorded carving a beech leaf for eight hours on the 14th. On the 15th he finished the beech and moved on to an elm leaf. Working 48 hours a week, he records his progress. The vision of the completed gate, welcoming visitors to this unexpected garden in the midst of a mossy, ledgy, forested hillside, must have sustained Gus as he labored on this particular project. The adjacent Thuya Lodge, a historic summer home formerly owned by landscape designer and civil engineer Joseph Curtis, had been open to the public since 1931. Since the opening of the gardens in 1962, Gus’s carved gates have welcomed visitors to both the lodge and the garden.^7

Thuya Gates, 2024, photo courtesy of John Meader.

Detail examples of Thuya Gate panels. First row: rudbeckia, owl, jack-in-the-pulpit, pitcher plant, bittersweet, grouse.

Second row: woodpecker, ash leaf, three fish, beech leaf, cow lily, and frog, water lily. Photos courtesy of Benjamin Meader.

Throughout the 1950’s various island groups had been working to rebuild, relocate, and reopen neglected island trails, both within Acadia National Park and outside its boundaries. In 1958, a large bequest to support ongoing trailwork in Northeast Harbor and Seal harbor had brought about “a flurry of trail activity.”^8 Gus worked on several of these trails, among them Brown Mountain, Schoolhouse Ledge, Hadlock, and Jordan Pond trails. In his logbook, he wrote of his work rebuilding trail sections: placing new sign posts, cutting brush along the trails, laying new corduroy trail, and “sawing bog spruce.”^9

As both new and improved trails were completed, funds were allocated for the creation of an updated Island trail map. The Mount Desert Chamber of Commerce, familiar with Gus’s cartography work, commissioned him to create two revised maps of the trails. Gus Collaborated with Acadia National Park authorities to produce both the Path and Road Map of the Eastern Part of Mount Desert Island Maine, and the Path and Road Map of the Western Part of Mount Desert Island Maine. Gus’s maps appear in the Olmsted Center’s Pathmakers: Cultural Landscape Report for the Historic Hiking Trail System for Mount Desert Island which states “The Phillips maps series was begun in 1964 and illustrates paths within and outside the park, similar to the discontinued VIA/VIS [Village Improvement Association/Village Improvement Society] maps.”^10 It also says, “This was…the first complete map since Turner’s 1941 Joint Path Committee map….The park service produced maps in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, but without topography, they were inferior to those produced by the AMC [Appalachian Mountain Club] and Augustus Phillips.”^11

Path and Road Map of the Western Part of Mount Desert Island Maine, and the Path and Road Map of the Eastern Part of Mount Desert Island Maine, 1975 editions.

Maps courtesy of Northeast Harbor Library.

In January 1964 Gus shared his love of storytelling with writer Richard Lunt who interviewed him for a book he was writing called Jones Tracy, Tall-Tale Hero from Mount Desert Island. ^12 Gus talked about knowing Jones and shared some of Jones’s stories as he remembered them. His version of “Shingling in the Fog” is pure delight.

Once in a while we have a heavy fog in our neighborhood and you have to work quite fast to keep warm. These Maine fogs kind of, kind of cut through you, especially in the late fall of the year when the temperature starts to drop. So, one of these boys, and I don’t remember who it was. It could have been Jones Tracy. I think it was possible that he was the hero. Well, he had a time limit on this shingling job or he wouldn’t have, he wouldn’t have shingled on the foggy day I’m sure. Well, he, he was trying to hurry to get the job done, and he got shingling away and he said the nails went in awfully easy along the last of . . . but still he was hurrying up and finally he begun to get hungry, thought it must be dinner time. He hadn’t looked at his watch and he did look at it and yes it was way past dinner time so he started to slide down off the roof towards the staging and he landed ten feet off one end of the building. He’d shingled out ten feet beyond the end of the roof. Fog was so thick, held that, held those shingles right up. I suppose also the fog was so thick that it kept him from falling down real fast.^13

As Gus ages, he wonders how he has found the time to draw, paint, and publish so many maps over the past few years. Researching the areas he wanted to feature, creating each map, and then selling the printed copies to customers new and old helps fulfill him and keeps him going. For as long as he can, he will continue to explore Maine, swap stories and tongue twisters with both new and old friends on his delivery routes, and take in all the scenery, flora, and fauna that Maine provides. It never ceases to sustain him.

Gus’s map “Sunrise on Acadia,” 1966. The original painted map hangs in the Northeast Harbor Library, photo by John Meader.

The Little House, photo courtesy of Cathy Jewitt.

Now Sunrise on Acadia, and maps of Penobscot Bay, Moosehead Lake, and the Allagash Wilderness, among others have been added to the Phillips collection of maps.^14 Consequently, large printing bills and the costs associated with running his business mean he has significant funds going out. He needs to keep working in order to keep money coming in. Among the ups and downs of the past decade, that truth remains a constant.

Another annual source of income is derived from renting out their house each summer. Known by the family as the big house, the property is advertised for rent as the Phillips Cottage. During these summer months he and Mary move into their little house, located behind the big house.

Mary and Gus, circa 1960’s, photo courtesy of Cathy Jewitt.

Gus knows that moving each spring and fall is wearing on both him and Mary. But he loves tending to his vegetable garden, apple trees, and berry bushes by the little house, and sharing whatever's ripening with friends and neighbors. He loves having his grandchildren come for a visit in any season, but during the summer there are activities unique to the little house.

In the summer his grandchildren race up and down the dirt drive on the stilts he made for them. He takes them into the garden, where he makes them trumpets from squash vines. Cedar shavings release their scent through the open door of his workshop, inviting the kids to collect handfuls of the curly shavings from the wooden floor to be fashioned into playthings. Sometimes Gus sets up a parachute tent by the ancient maple tree in the back field, where the wooden swing gets daily use.^15

All and all, Gus keeps moving forward into whatever life has in store for him. With Mary beside him, he will live life to its fullest—even when it overflows at times.

Authors’ Notes:

Gus, Cathy, Mary, and Alan, 1955, photo courtesy of Cathy Jewitt.

Maya Angelou said, “You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”^16 Propelled by an innate creative energy, Gus naturally incorporated art into his work and interactions with others. Consciously or not, he preserved the culture and history of Maine, leaving a legacy in maps and postcards, woodcarvings and words. Described by those who knew him as genuine and generous, but not generally gregarious, Gus nevertheless overcame his reticence at times. If the opportunity arose for storytelling or recitation, then he’d oblige with a tall tale, tongue twisters, or stories at bedtime for a granddaughter who needed help falling asleep.

—Cathy

My first visit to Acadia National Park and Mount Desert Island was on July 20, 1969. I was 10 years old. I remember the picnic we had before driving up Cadillac Mountain, visiting Thunder Hole, the trip around the Park Loop Road, and walking the streets of Bar Harbor searching for postcards of the sights we’d seen that day. I didn’t know Gus’s postcards from anyone else’s, but I knew what I liked—postcards with good pictures, but no words over the pictures. That ruined the card as far as I was concerned. Today, as I look over Gus’s postcards from MDI, I remember several that were among the ones I bought that day: Thunder Hole, an aerial of Bar Harbor, Sand Beach, and Bass Harbor Light. It was a glorious day. My mom and dad were members of “Couples Club” at our church. The group would often arrange Sunday drives, where each couple and their respective families would go in their own car and parade along the highway to various destinations for a picnic and some scenic stops. This was one of those trips. I remember loving Acadia, but one of my strongest memories from that day was listening to the news on the car radio. It was July 20, 1969, the day the astronauts landed on the Moon. Neil Armstrong didn’t walk on the Moon and make his famous statement, “One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” until almost 11pm that night. I remember Mom and Dad let me stay up that night, but I was so tired from a big day on Mount Desert Island that the actual memory of Armstrong’s first step is a foggy one at best. Nevertheless, even today, whenever I visit Acadia National Park, I still think of the first moon landing and the grand day I had exploring one of Earth’s most beautiful islands.

—John

Special thanks:

To the Penobscot Marine Museum and Photo Archivist Kevin Johnson for image use, preserving the Phillips Collection, and continued support; the Northeast Harbor Library and Archivist Daniela Accettura for continued support and image use; The Mount Desert Land and Garden Preserve for their preservation, maintenance, and sharing of both Asticou Azalea Garden and Thuya Garden; the late C. Richard K. Lunt for recording and preserving recollections and tall tales told by Mount Desert Islanders; Ben Meader for technical support and hosting; John Meader for photography; the late Mary Jane Phillips Smith, Gus’s daughter, for preserving and sharing Gus’s legacy; the late Frederick A. Phillips, Gus’s son and Cathy’s father, for preserving family stories and memories in his journals and inspiring her to keep Northeast Harbor journals of her own.

Notes:

1. Cathy Phillips Jewitt, Evening Slide Shows, Northeast Harbor journals, owned by author.

2. “Visitation Numbers,” National Park Service, accessed June 5, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/visitation-numbers.htm

3. Luther Phillips, “Bird’s Eye View of Isleford,” Card Cow, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.cardcow.com/829803/islesford-maine-birds-eye-view/

4. Gus Phillips, “Baker Island Light,” Card Cow, accessed June 14, 2025, Card Cow, https://www.cardcow.com/412596/baker-island-light-islesford-maine/

5. Gus Phillips, “Breaking Waves Dash High,” Card Cow, accessed June 18, 2025, https://www.cardcow.com/60233/breaking-waves-dash-high-little-hunters-beach-mount-desert-island-maine/

6. Gus Phillips, “Northeast Harbor, Yachtsman’s Paradise,” Card Cow, accessed June 18, 2025, https://www.cardcow.com/60238/northeast-harbor-maine/

7. Logbook kept by Augustus “Gus” Phillips, owned by Cathy Jewitt.

8. Margaret Coffin Brown, preparer, Pathmakers - Cultural Landscape Report for the Historic Hiking Trail System of Mount Desert Island Acadia National Park, Maine HIstory, Existing Conditional, & Analysis (Boston, Massachusetts, Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service, 2006), 156.

9. Logbook kept by Augustus “Gus” Phillips, owned by Cathy Jewitt.

10. Margaret Coffin Brown, preparer, Pathmakers, 157.

11. Margaret Coffin Brown, preparer, Pathmakers, 156.

12. C. Richard K. Lunt, Jones Tracy, Tall Tale Teller From Mount Desert Island (Northeast Folklore X, 1968).

13. Augustus Phillips, January 2, 1964, recorded interview, C. Richard K. Lunt, Jones Tracy, Tall Tale Teller From Mount Desert Island (Northeast Folklore X, 1968), 28-29.

14. Sunrise on Acadia, and other Phillips maps at the Penobscot Marine Museum, Searsport, Maine, https://penobscot-marine-museum.square.site/product/phillips-sunrise-on-acadia/811?cs=true&cst=custom and information about the Penobscot Marine Museum’s Phillips Collection, https://penobscotmarinemuseum.org/phillips-collection/.

15. Cathy Phillips Jewitt, Northeast Harbor journals, owned by author.

16. Maya Angelou, “Interview: Maya Angelou– a Passionate Writer Living Fiercely with Brains, Guts, and Joy,” interview by Judith Paterson, Vogue, September 1982, https://archive.vogue.com/article/1982/9/interview-maya-angelou-a-passionate-writer-living-fiercely-with-brains-guts-and-joy.